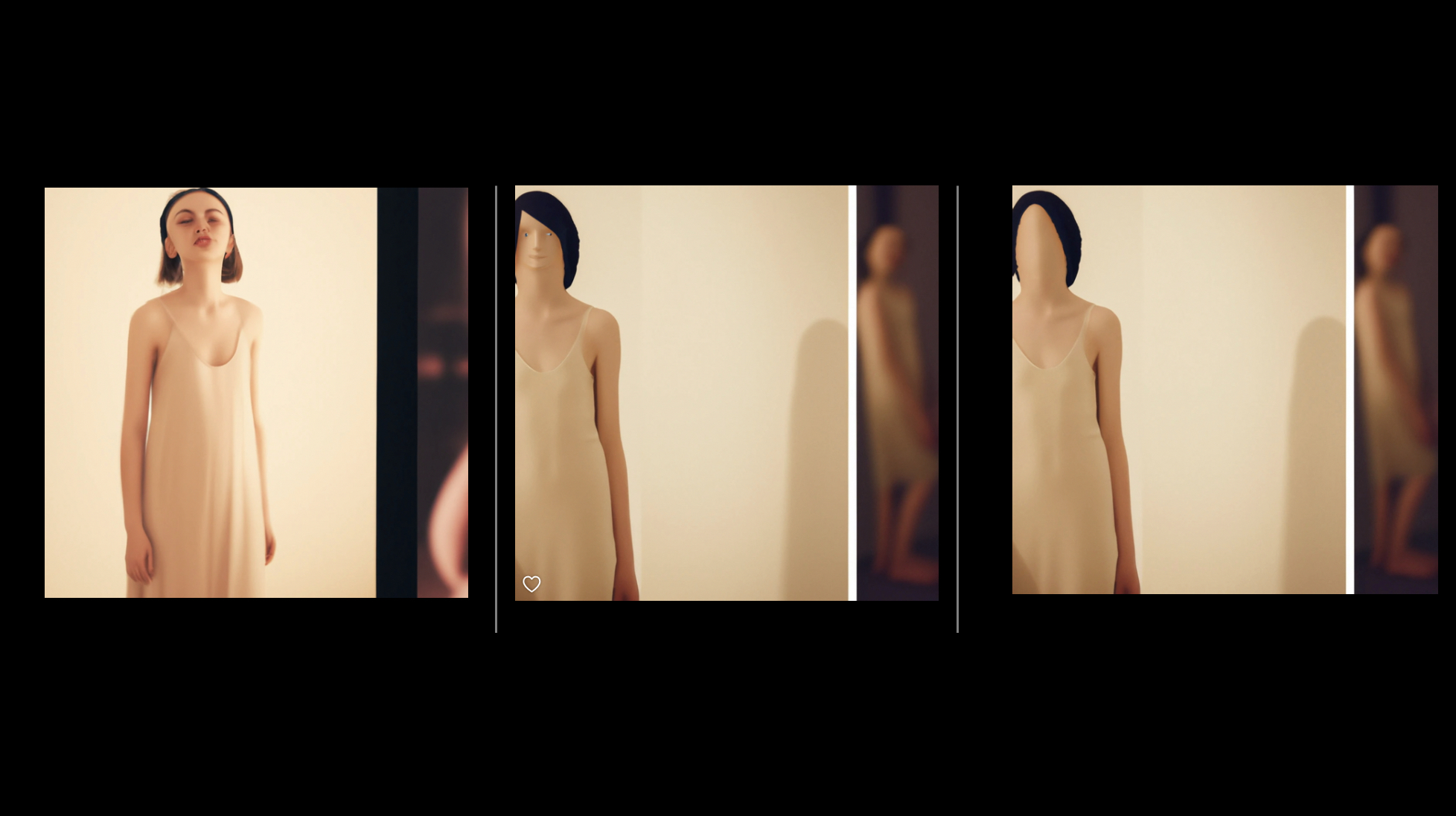

“Becoming Beige,” by Amy Selwyn and DALL-E 2 (Human and AI

LouLou’s Story

I was always stubborn. I wore my impatience right there on my face. My mother and father warned me: “You’ll never be considered attractive with that kind of an attitude.” And I advised them, more than once, “Marriage is not an achievement.”

They sent me to Dr. Wellhaven, a psychiatrist. I loved her name. Norwegian. She had the classic shrink set-up: some African art in a cream-on-cream, sound proofed office. Kleenex strategically positioned. Clocks, too.

Dr. Wellhaven agreed with me about the overvaluing of marriage as a life goal. She wondered why I wore dresses that looked like slips. She explored whether I felt compelled to “adhere to certain norms for women and physical appearance.”

I shook my head. No. Dr. Wellhaven continued.

“There is a beauty standard. She projects a very particular kind of image,” she said.

Dr. Wellhaven described this beauty standard in such a way that I envisioned a life-sized portrait of what women the world over longed to look like.

“Or maybe,” I said to Dr. Wellhaven, “what women the world over believe other people, especially men, want us to look like.”

We agreed to discuss this the following week.

A little while after I started with Dr. Wellhaven, I met Bob. A blind date. Except I went in eyes wide open. I figured I’d have dinner with this guy (“Such a catch!” said my mother. “He went to Yale!”) and hot foot it home in time for an episode or two of “My Lottery Dream House.”

Surprise, surprise. Bob and I had fun on that first date. And the second. And the third. Bob made me laugh. And he tipped very generously. I loved that. Showed good character. So we kept dating.

Smart, confident, popular Bob. I had no idea what he saw in me, frankly. I saw myself as moody and headstrong and dissatisfied. But Bob seemed to see past all of those ideas. He praised my body (“So thin! So lithe! Like a ballerina!”). Said he loved a woman with a bob haircut. I’d been hoping Bob would notice my artistic bent, but it was more the physical stuff.

Bob found it hard to believe that anyone could find me headstrong. “You?” Handsome Yalie turned investment banker (there was a Harvard MBA in there, too) Bob laughed. “You’re adorable and flexible and just about perfect.”

One night, in Bob’s apartment, after he had fallen asleep, his arm wrapped around me (protectively? possessively?) I saw a portrait materialize on the wall opposite Bob’s bed. (Bob jokingly referred to his bed as “my workbench,” which I found cringeworthy.) The portrait showed me a fuzzy, nondescript version of somebody who looked a lot like me.

“I’m the beauty standard,” she whispered. “I’m here to guide you to a happy life.”

I wasn’t quite sure what to make of her, but I awoke the next morning and even before heading to the bathroom to brush my teeth and pee, I was aware of feeling slightly different. I felt vague. It wasn’t a bad feeling. It was more like when I started on Lexapro and could feel the edges starting to smooth out. There wasn’t a trace of any ornery feelings. In fact, I wasn’t aware, that first morning, of feeling much of anything at all.

The beauty standard, still watching me from the wall in Bob’s bedroom, winked as I dressed. “You got this, girll!” she said.

Weeks passed. Then months. I moved in with Bob. Even though I kind of remembered hating black leather couches (too sports bar for me), I agreed (without reluctance) when Bob suggested we buy two of these massive things for our living room. I couldn’t quite remember what it was I used to like.

When Bob proposed, with a “substantial” (3-carat) emerald cut diamond set in platinum, my mother cried and my father called his golf buddies, and they both suggested we do everything at The Club. At that, I felt a frisson of something unpleasant — an association with something I held in low esteem. But I couldn’t figure out why I was having that reaction. I pushed it away.

I went to Bergdorf Goodman and my parents bought me a very expensive wedding gown. (“She’s a size 2! Literally everything looked great on her, my mother reported.) My mother told me I looked like Keira Knightley, the British actress, and said that with a little bit of padding in the bra I’d be the truly perfect bride.

I noticed the beauty standard was now following me around, wherever I went. As much a part of my spacial needs as my Birkin bag, a present from my future mother-in-law.

I noticed, too, that I no longer showed any emotions at all. I was a clean slate. No dissatisfaction, no opinions, no affect at all. My face started looking, well, featureless. And no one commented on this weird fact. In fact, I started receiving more compliments than ever.

Bob told me he was so proud of me. He said I was perfect and he couldn’t imagine a more wonderful life partner.

Bob said I didn’t “have to” work. He made tons of money, that’s the truth. Seven figures. I didn’t have any ideas about something I might want to go out and do, so I mostly just stayed at home. Or went shopping. I admit I felt pretty good when sales people would say, “You’re a perfect size 2. You can wear any of this year’s styles!”

Every once in a while, after we were married and we would sit on our very expensive oversized black leather couches, Bob reading Barron’s and me scrolling Facebook, I would nearly catch a memory floating by. Fleeting! I remembered being angry. I remembered a face full of rebellion.

I quickly pushed away the thought. I suspected it would ruin everything. To be honest, it was so much easier just being beige. And needing nothing.

This is a collaborative work, created by my imagination and DALL-E 2, a generative AI technology that enables users to create images with linguistic prompts. Rather than looking through a viewfinder (camera) or whipping out my phone and setting up the shot on the phone screen, the artist conceptualizes the work and feeds the AI a series of words and phrases from which to create a unique image. Metaphor and poetic use of language play a big part in working with AI as a visual artist.